Who is John Maynard Keynes?

Who is John Maynard Keynes?

JOHN MAYNARD KEYNES was one of the most influential thinkers and international statesmen of the 20th century. He was, as the famous writer Leonard Woolf noted, ‘a don, a civil servant, a speculator, a businessman, a journalist, a writer, a farmer, a picture dealer, a statesman, a theatrical manager, a book collector’.

And he was also one of the greatest Economists who had a profound impact on economic theory and policy around the world. He made major contributions to intellectual, political and cultural life and continues to be one of the seminal source thinkers of all times.

This interactive e-book is a tribute to this great mind.

The Aphorist

The Aphorist

The Life

The Life

The Prodigious Son

The Prodigious Son

KEYNES was born on 5 June 1883 in Cambridge, England, to an upper-middle-class, intellectual family. His father John Neville Keynes worked as a lecturer in moral sciences at the University of Cambridge. His mother Florence Ada Keynes was a local social reformer who became the town’s first female mayor. Keynes had two younger siblings, Geoffrey Keynes and Margaret Neville Keynes.

From an early age, he showed great articulacy and brightness: when he was four he asked his mother: ‘How do things get their names?’ At the age of nine he had already finished book 1 of Euclid and had algebra as his forte.

In 1897, Keynes earned a King’s Scholarship for Eton after being placed tenth among the scholars. During his first year he won ten prizes and eighteen in the next. By the time he left Eton, he owned over 300 books and was highly engaged in exclusive discussion groups – a habit that would continue throughout his life.

In 1902 Keynes received a scholarship to study Mathematics at King’s College Cambridge University. He studied Economics for only eight weeks and was taught by Alfred Marshall, who would have major influence in his early economic works. While in Cambridge he met Lytton Strachey and Leonard Woolf, who would become lifelong companions.

With universities training young men to suit the needs of an imperial nation, it was a natural path for Keynes to join the civil service when he left Cambridge in 1906. After coming second in the entrance examination, he worked in the India Office as a junior clerk. Two years later, he quit the civil service and returned to Cambridge after being offered a lectureship in Economics at King’s College.

The Bloomsbury Intellectual

The Bloomsbury Intellectual

THE Bloomsbury Group was a small gathering of modernist artists and intellectuals who challenged Victorian and Edwardian social conventions, sexual taboos and views of the world. Its core members included the writers and critics Virginia Woolf, Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, and Clive Bell, and the artists Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry and Duncan Grant, among others.

Bloomsbury men and women talked and listened in equal terms and valued each other’s intellect and wit. Their core value was that what mattered most was ‘states of mind’.

This group of friends and lovers had an extraordinary and enduring impact on 20th century culture: ‘in a hypocritical society, they have been indecent; in a conservative society, curious; in a gentlemanly society, ruthless and in a fighting society: pacifist’ (Raymond Mortimer).

(Dorothy Parker)

The Sensual Man

The Sensual Man

KEYNES sex life was more than a mere supplement of the rest of his life, it was his life because it arose from his fundamental philosophy of living a good life. Also, his romantic and sexual relationships reflected his attempt to escape from the shackles of Victorian – Edwardian Britain. From his days in Eton and Cambridge until the early 1920’s, most of his sexual affairs were with men, including the painter Duncan Grant and writer Lytton Strachey.

Famously, he kept a log of his sexual encounters in his diary, including initials, nicknames or descriptions. This is rather startling for a time when any homosexual act was considered unlawful such that, as he wrote in a letter to Duncan Grant: ‘I had a dreadful conversation on Sunday with my mother and Margaret about marriage…and had practically to admit to them what I was!’

The Devoted Husband

The Devoted Husband

IN 1918 Keynes met Lydia at a party to celebrate the Ballets Russes of Diaghilev in London. Three years later, enthralled by Lydia’s performance in Sleeping Beauty, Keynes sat several times on his own in the stalls. After a backstage meeting, which he sought, he asked her out to dinner. Two weeks later he found an excuse to accommodate her in an apartment above his in Bloomsbury.

This unexpected love affair appalled his Bloomsbury friends. A year after marrying they had a miscarriage and subsequently never had children. Although many of Keynes’s gay friends also got married in early middle age as way of ‘disguising’ their sexuality, Keynes’s marriage to Lydia was genuine.

As noted by Virginia Woolf, ‘Maynard is passionately and pathetically in love, because he sees very well that he’s dished if he marries her, and she has him by the snout’ (1924).

The Courageous Official

The Courageous Official

WITH the outbreak of The Great War in 1914, Keynes joined the Treasury to work on external financing for the war. This action disgusted his Bloomsbury friends who were against Britain fighting and was most difficult for him. He was in the British delegation to the Paris Peace Conference of 1918 which led to the Versailles Treaty.

He resigned in protest over the punitive reparations being imposed on Germany which he regarded as vindictive. He saw the behaviour of the Allies leaders as immoral and incompetent. In response he rapidly wrote and published The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919) in which he predicted that the reparations issue would trigger a desire for revenge among Germans, as proved to be the case in the 1930s.

The book became an international best-seller, putting economics on the map for the general public and ultimately ensuring that policies after WWII were wiser and more humane. The book also made Keynes’s international reputation.

(John Maynard Keynes)

The Businessman

The Businessman

KEYNES made, lost, and made again a fortune by speculating in the financial and commodity markets. He also had an impressive portfolio of investments. His trading activities included cotton, metals, rubber, jute, sugar, wheat, and company shares.

Keynes also acted as board member for a number of companies. He was Chairman of the National Mutual Life Insurance Company, Director of the Provincial Insurance Company, and Director of various investment trusts.

In 1924 he was made Bursar of King’s College, Cambridge, where he greatly improved the College’s investments performance. He also earned a significant income from his books and journalism.

He frequently wrote on his economic views for the Manchester Guardian and The Nation. He always retained copyright of his writings to control publication of his work and the fees he could charge.

(John Maynard Keynes)

The Arts Patron

The Arts Patron

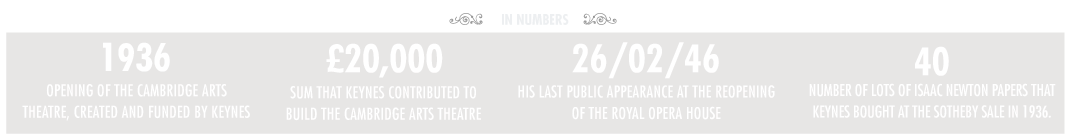

KEYNES used his wealth and influence to buy pictures and books, to help painters and also to establish new institutions across Britain. He raised Treasury money for the Royal Opera House and founded the Cambridge Arts Theatre and Britain’s Arts Council.

In 1918, having persuaded the government to fund the purchase of art for the National Gallery and having obtained a considerable sum from the Treasury, he was accompanied by the Gallery’s director to Paris to buy at an auction of Edgar Degas’ personal collection of paintings.

Back in England, he announced to Duncan Grant and Bunny Garnett that he had a Cezanne painting in his suitcase but that ‘it was too heavy for me to carry, so I’ve left it in a ditch, behind the gate’. Grant and Garnett rushed to the gate to retrieve the expensive painting and returned in triumph with it.

(Virginia Woolf)

The Writer

The Writer

KEYNES’S passion for writing can be traced back to his schoolboy explorations of his family genealogy. Throughout his life, he published books, pamphlets, articles and letters for newspapers, papers and essays in academic journals, and exchanged correspondence with influential figures of the time, such as George Bernard Shaw.

He also wrote distinguished and memorable biographical essays, including an influential one on Isaac Newton and the renowned obituary of his mentor Alfred Marshall. His writings also highlight his skills as an eye witness to international diplomacy.

He took part in a vigorous debate with George Bernard Shaw about socialism in the USSR in The New Statesman and Nation following the publication of G. H. Well’s interview with the dictator Josef Stalin in 1935. Keynes described the interview as a man (Wells) struggling with a gramophone (Stalin) which is not capable of recognising the flaws of its own thinking.

(John Maynard Keynes)

The Visitor

The Visitor

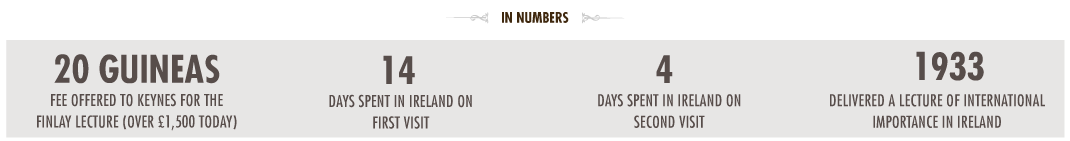

KEYNES first came to Ireland in 1911 with a group of fifty Liberal Party MPs for a two-week tour. Dissatisfied by their company, he departed for a week by himself which, as he later said to his mother, helped convert him to Home Rule. The second visit, in 1933, was a major political event in the midst of the economic war between Ireland and the United Kingdom.

Keynes not only saw himself playing the role of a peacemaker, but also used his lecture at UCD to explore the issue of free trade versus protectionism. Unprecedentedly, the audience was formed by both sides of Ireland’s fractious political elite. Among Keynes’s typically hectic schedule was a dinner after the lecture during which he was called to the phone. On his return he announced that the U.S. had just left the Gold Standard. The natural silence which followed was broken by poet Oliver St. John Gogarty asking: ‘Does that matter?

(John Maynard Keynes)

The World Shaper

The World Shaper

KEYNES’S best-known work, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, was published in 1936 and soon became the seminal work of the second half of the 20th century. Towards the end of WWII he was involved in the negotiations that were to shape the post-war world. In 1944 he led the British delegation to the conference at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire.

He played a significant role in the planning of a new international order, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. On the morning of Easter Sunday, 21 April 1946, he had a final heart attack as Lydia brought him a cup of tea. He was 62 years old.

By the time of his death in 1946, his ideas and their interpretation were becoming a new orthodoxy and for the next 30-35 years would be adopted in some way by governments across the world.

The Keynesian Revolution and The Age of Keynes, as his effects were branded, resulted in virtually all economists having to engage in one way or another with Keynes’s thinking since then.

Keynes by Mike O’Donnell

Keynes by Mike O’Donnell

All the sketches in this interactive e-book are copyrighted and were drawn by the talented artist Mike O’Donnell exclusively for this commemorative project.

Please, contact Mike O’Donnell directly for permission to use any of his work and for commissioning your own work from him. Sample of his artwork and contact details can be found on his website Courtsketcher.com and on his Twitter @mikodonnell.